"Teleflocking" is an adaptation of "Flocking," which I developed based on my experience with Theatrical Mime. In the original version, everyone stands in a loose clump, facing the same direction, and copies one person’s movement. The person you copy changes as the direction you’re facing changes. This exercise builds connection, expands awareness, and promotes shared leadership.

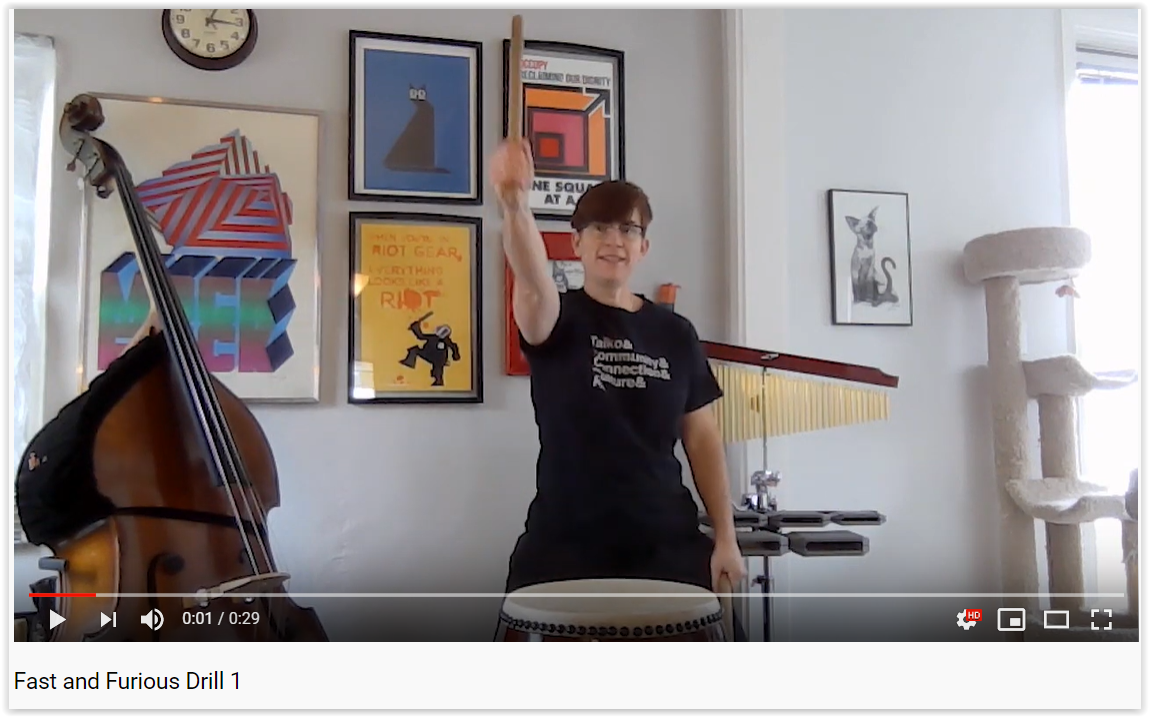

Below is the way Kristin and I have adapted Flocking to the virtual realm. These directions are based on using Zoom, and the video shows Teleflocking in a recent Saturday morning Community Taiko Tap-Along Play-Along. (Shout out to Viv, Eileen, Noriko and Chiara for volunteering to lead!)

Have everyone turn on Gallery view.

Ask for volunteers to lead. 4-5 is good for groups that don't all know each other, more works if people are well-acquainted. Leaders need to have their video on.

Say the volunteers’ names in the order they'll be leading, and ask each of them to wave at their camera when you say their name.

Start moving. Participants copy you. After 10-15 seconds, say the name of the next leader.

Follow the next leader. After 10-15 seconds, say the name of the next leader.

Repeat #5 until all volunteers have had their turn.

It only takes a minute or two, and it’s a great activity. The video delay in Zoom creates moments both beautiful and hilarious. Teleflocking brings about a moment of connection that’s precious in this time when we’re all isolated from one another and our groups.

I’d love to hear about it if you try Teleflocking in one of your virtual classes. Happy teaching!